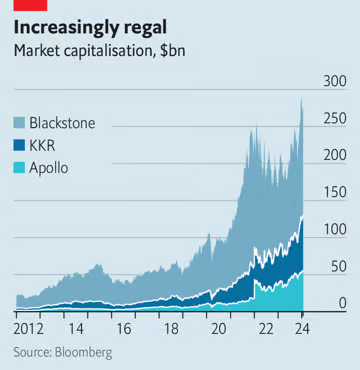

Blackstone, one of the top Wall Street titans, went public on the New York Stock Exchange in the summer of 2007. Unfortunately, this timing was unfortunate as it was just before the global financial crisis hit. As a result, the firm’s shares experienced a significant decline, losing almost 90% of their value by early 2009.

This decline coincided with a difficult period for Wall Street in general, as KKR and Apollo, two other prominent members of America’s private-markets troika, also faced challenges during this time. KKR listed on July 15th, 2010, which happened to be the same day Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Act, an important legislation that aimed to revamp bank regulation. Apollo, on the other hand, went public eight months later. Despite these setbacks, all three firms emphasized to their investors that their expertise lay in private equity, which involves acquiring companies using debt.

However, with the economy bouncing back, private-market companies have thrived and become the dominant players on Wall Street. These Wall Street titans have been investing more and more money in credit, infrastructure, and property, resulting in a total of $12 trillion in assets under management by 2022. Over the past decade, firms like Apollo, Blackstone, and Kkr have seen their assets rise from $420 billion to $2.2 trillion.

In 2023, private equity firms’ diversified portfolios led to a remarkable 67% average increase in their shares, despite higher interest rates causing a slowdown in buy-outs. The fund-raising and investment model, whether for acquiring companies or providing loans, rarely raises concerns among regulators. Private equity has its critics, but the losses are borne by the institutional investors of the fund. Moreover, fund managers who face embarrassment find it challenging to secure future funding. Therefore, there is minimal risk to financial stability.

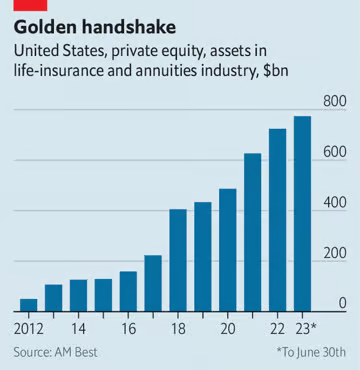

The current trend in the industry is causing a major shift in how things are done. Wall Street titans are now purchasing and forming partnerships with insurance companies on a larger scale than ever seen before. This change significantly alters their business models as they expand their lending operations and sometimes their overall financial standing.

The primary focus has been on the $1.1 trillion fixed annuities market in America, which is a retirement-savings product offered by life insurers. However, Morgan Stanley, a banking institution, believes asset managers may eventually pursue insurance assets worth $30 trillion globally. Regulators are concerned that this expansion may increase the risk in the insurance industry. Is the increasing involvement of Wall Street titans a result of opportunistic investors taking advantage of a crucial sector of the financial system? Or is it actually the intended consequence of a more tightly regulated banking system?

Wall Street giants Apollo, are at the forefront of financial innovation. Back in 2009, they made a strategic investment in Athene, a newly established reinsurance company based in Bermuda. Over the years, this partnership has flourished, and by 2022, when Apollo merged with Athene, they had become the leading seller of fixed annuities in the United States.

Currently, Apollo oversees a staggering $300 billion in assets for its insurance business alone. In the first three quarters of 2023, the firm’s earnings from investing policyholders’ premiums, known as “spread-related earnings,” amounted to a substantial $2.4 billion, making up nearly two-thirds of their total earnings.

Being inspired by successful strategies is a smart move in the financial world. kkr recently acquired Global Atlantic, an insurance company, following in the footsteps of Apollo. On the other hand, Blackstone prefers to invest in minority stakes. With $178 billion of insurance assets under its management, Blackstone earns substantial fees. Brookfield and Carlyle have also supported large reinsurance companies based in Bermuda.

tpg is currently in discussions regarding potential partnerships. Even smaller investment firms are getting involved in this trend. Investment firms now own life insurers with assets totaling almost $800bn. It’s worth noting that the flow of activity is not one-sided, as Manulife, a Canadian insurer, announced its plan to acquire CQS, a private-credit investor, in November.

Many people view partnerships between life insurers and private-market buyers as mutually beneficial. In developed countries, there is a growing concern about the lack of retirement funds. Defined-benefit pensions, which guarantee income for retirees, have decreased in popularity for several years. Annuities provide individuals with a way to plan for their future financial needs.

Life insurers are happy to transfer this business to private-markets buyers. By doing so, they can free up their balance sheets for activities such as share buy-backs or other insurance activities that require less capital. At the same time, private-markets firms acquire a large amount of assets and earn stable fees for managing them.

However, there are potential dangers for both policyholders and financial stability. The American insurance industry’s regulation primarily falls under individual states’ jurisdiction. Unfortunately, these states do not possess the same level of efficiency and expertise as the Wall Street titans in the private markets.

The National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC), which consists of state regulators, establishes crucial standards such as the required capital for insurers. In 2022, the NAIC implemented a plan to investigate 13 regulatory considerations regarding life insurers owned by private equity firms. These considerations include examining their investments in private debt and their tendency to engage in offshore reinsurance deals.

Ever since then, additional individuals have expressed their worries. In December, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) advised lawmakers to eliminate the chance for regulatory arbitrage by implementing uniform capital standards and monitoring systemic risks in the sector. A study conducted by researchers at the Federal Reserve suggests that the collaboration between life insurers and asset managers has heightened the industry’s susceptibility to a sudden upheaval.

The researchers went so far as to draw comparisons between insurers’ lending practices and those of banks before the financial crisis. Bankers, who often complain about being excessively regulated, may agree with these findings.

Insurers have an advantage over banks when it comes to withdrawing funds from annuities. Unlike bank deposits, annuities cannot be easily or cheaply withdrawn by policyholders. However, there is still a possibility of a “run” on a life insurer, although surrender fees payable for early withdrawals make it less likely.

Wall Street titans in the private markets believe that this characteristic of insurers makes them ideal buyers for assets with higher yields that are not easily traded. Therefore, they are shifting insurers’ investment portfolios away from easily tradable government and corporate bonds, which dominate America’s debt market, and towards “structured” credit that is backed by pools of loans.

The structured credit market in the United States, excluding government-backed property debt, is valued at $3 trillion. This market consists of paper promises that are backed by a mix of real estate borrowing and other assets, such as collateralised-loan obligations (clos) formed by bundling corporate loans together. The concept behind securitization is straightforward: if the correlation of defaults between risky loans is expected to be low, it allows for the creation of more investment-grade credit that can be offered to investors.

As per the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC), by the end of 2022, approximately 29% of bonds held by insurers owned by private equity firms were structured securities. This is significantly higher than the industry average of 11%. These types of assets pose challenges not only in terms of selling them during market panics but also in valuing them accurately.

Fitch, a ratings agency, conducted an analysis and found that a substantial portion of these assets were valued using “level 3” accounting, which is typically used for assets that lack clear market values. On average, investment firms owned ten insurers that had 19% of their holdings valued using level 3 accounting, which is approximately four times higher than the broader sector.

The top financial firms on Wall Street not only purchase private debt but also create it. Some of these firms have significantly expanded their lending activities to bolster the balance sheets of their affiliated insurance companies. For example, Apollo has originated nearly half of Athene’s invested assets by acquiring 16 different companies, including an industrial lender in Blackburn, England, and an aircraft-finance operation previously owned by General Electric.

Similarly, kkr’s partnership with Global Atlantic has resulted in a seven-fold increase in the size of its structured-credit operation since 2020. Private-market firms’ involvement in securitisation may continue to grow if new banking regulations, referred to as the “Basel III endgame,” lead to higher capital requirements for traditional banks engaging in these activities.

One concern relates to the performance of this debt in a prolonged period of financial trouble. If the credit ratings of these debts are downgraded, it would result in higher capital charges. Additionally, if there are high-profile defaults, policyholders may withdraw their funds. Despite the market’s anticipation of interest rate cuts in 2024, many borrowers with floating-rate loans, particularly those in the commercial property sector, are still experiencing the negative impacts of increased payments.

It is true that the structured credit market has become less complex since the financial crisis, with the elimination of structured securities backed by other structured securities. Insurance companies typically purchase the investment-grade portions of securitized products, which means that any losses would initially be absorbed by those lower in the hierarchy of cash flows.

However, not everyone is convinced of the safety of these approaches. Craig Siegenthaler from Bank of America argues that investors cannot truly assess the reliability of these methods until they have undergone a rigorous stress test. Critics also point out that regulations struggle to keep up with financial innovation, particularly in the insurance sector. Currently, insurers are required to hold less capital after purchasing each tranche of a collateralized loan obligation (CLO) compared to buying the underlying risky loans themselves. This incentivizes investments in complex and illiquid products.

The special one

One example of a company with illiquid investments is Security Benefit, an American life insurer that was acquired by investment firm Eldridge. Eldridge is led by Todd Boehly, who also owns Chelsea Football Club. In September, nearly 60% of Security Benefit’s $46 billion worth of financial assets were categorized as “level 3”, indicating their illiquidity. According to data from s&p Global, Security Benefit’s $26 billion bond portfolio only includes $11 million worth of Treasuries.

Similar to other insurance companies, Security Benefit has purchased bonds from an asset manager that is affiliated with them. Among their holdings are several collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) created by Panagram, which is owned by Eldridge. The largest CLO held by Security Benefit is supported by $916 million worth of risky loans.

Once securitized, this portfolio generated over $800 million of investment-grade debt for the insurer’s balance sheet. Security Benefit states that their long-term liabilities have built-in features such as surrender charges, market-value adjustments, and lifetime withdrawal benefits, which provide significant protection against unexpected cash outflows. Additionally, they claim to have access to several billions of dollars in liquidity through institutional sources.

The presence of offshore reinsurance has made it more challenging for the insurance industry to evaluate investment risks. Moody’s, a ratings agency, has reported that nearly $800 billion worth of offshore reinsurance agreements have been made. These agreements involve one insurance company transferring its risk to another company located overseas, often to a captive offshore insurer that it owns. Bermuda is the preferred location for such deals due to its less stringent capital requirements. Interestingly, a significant number of these deals involve insurers associated with private-equity firms.

In the previous year, there were several significant reinsurance deals that took place, involving collaborations between established life insurance companies and reinsurers backed by private equity firms. For instance, in May, Lincoln National announced a $28 billion partnership with Fortitude Re, a Bermuda-based reinsurer supported by Carlyle.

During the same month, MetLife, another major insurer, revealed a $19 billion agreement with kkr’s Global Atlantic. The growing demand for offshore reinsurance was evident when Warburg Pincus, a prominent private equity firm, declared in September that it would establish its own operation on the island, with the support of insurer Prudential.

Northwestern Mutual, a prominent life insurer, expressed its concerns about offshore reinsurance transactions in a letter to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC). The company highlighted the potential negative effects, such as reduced transparency and weakened capital strength within the insurance industry. Recognizing these concerns, regulators have urged Bermuda to strengthen its regulations.

In response, British officials suggested new rules in November to restrict offshore reinsurance activities. Following this, Marc Rowan, the CEO of Apollo, acknowledged that certain offshore practices in the industry were worrisome. As Bermuda tightens its restrictions, Rowan expressed concerns that some firms might relocate to the Cayman Islands to exploit regulatory loopholes.

Italy has become a concerning case study for regulators, surpassing Bermuda in terms of worrisome situations. A British private-equity firm, Cinven, took over and merged various Italian life insurers starting in 2015. The resulting conglomerate, Eurovita, accumulated assets worth €20bn ($23bn) by the end of 2021.

However, as interest rates rose, the value of Eurovita’s bond portfolio declined, leading customers to surrender their policies in search of higher-yielding investments. This capital shortfall prompted Italian regulators to place Eurovita under special administration in March 2023, with some policies being transferred to a new company.

The problems faced by Eurovita were not caused by investments in private debt, but rather by inadequate management of assets and liabilities. Eurovita had weak measures in place to prevent policyholders from withdrawing money, and Cinven’s investment was made through a traditional private-equity fund rather than more complex transactions undertaken by larger asset managers. However, according to Andrew Crean of Autonomous, a research firm, European regulators have become more cautious towards private equity in the insurance industry following this incident.

Is it possible that there will be more financial crises in the future? The quick integration of private capital into the life-insurance sector makes it difficult to dismiss this possibility. The intense competition for assets might lead some private-markets companies to deviate from their usual focus on annuities and invest in riskier assets or liabilities that do not align well with their strategies. If an insurance company were to collapse, it could have a significant impact on the overall financial markets. While private markets have brought new energy to the insurance industry, regulators are concerned that they may also be compromising its safety.